The Digital Age

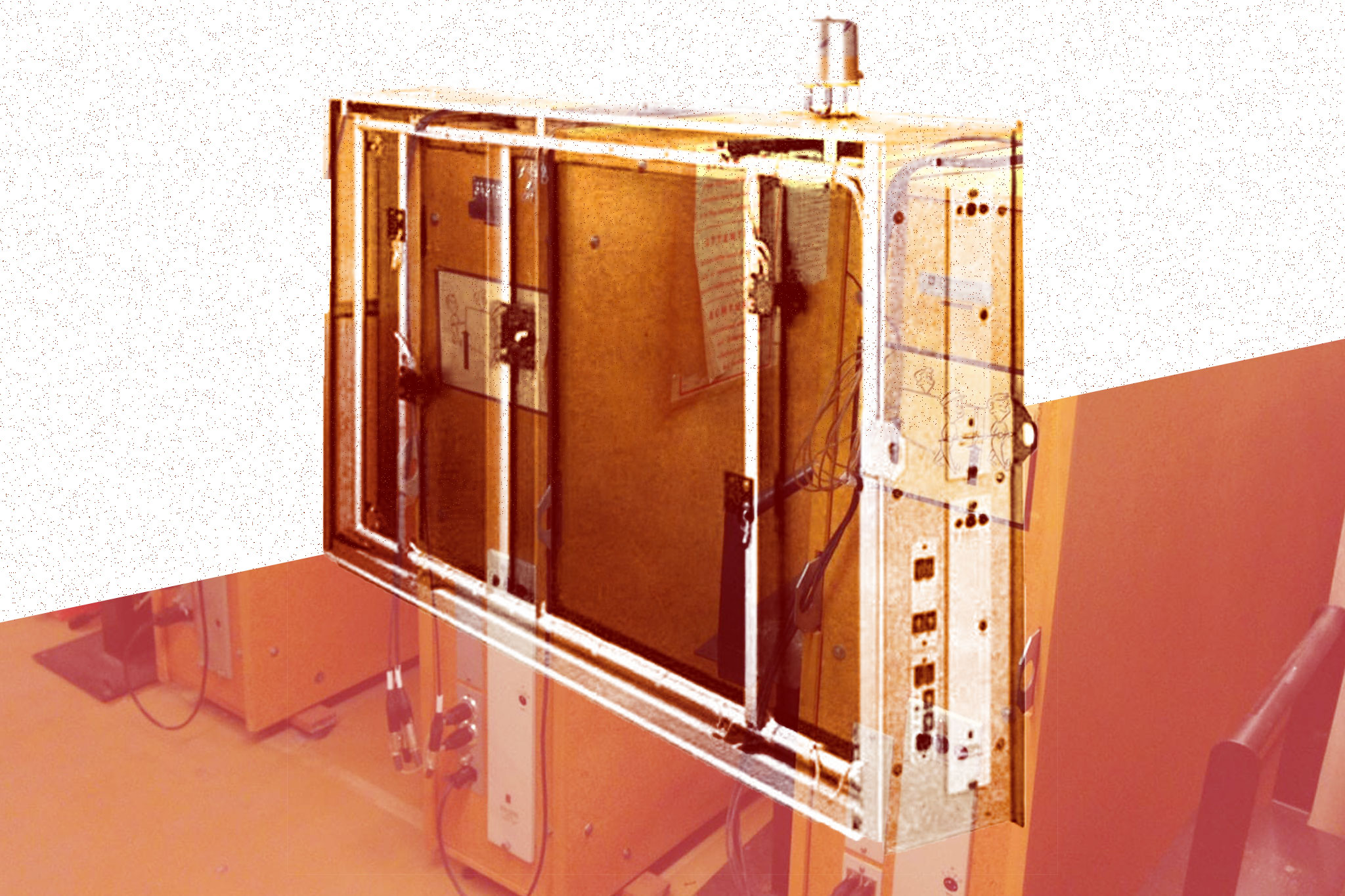

EMT changed the game once again in 1976 with the launch of the world’s first digital reverb, the EMT 250, built in conjunction with American manufacturer Dynatron. (In fact, 1972’s EMT 144 was the first digital reverb, but it was so rudimentary and under-supplied that it can be largely overlooked.) Marketed as a digital version of the EMT 140, the 250 was a comparatively mobile floor-standing unit that actually went several steps beyond the capabilities of its forebear, generating chorus, phaser and delay effects as well as reverb, and sounding absolutely phenomenal doing it. Marking a turning point in pro audio technology, the 250 was followed four years later by the EMT 251, which upped the processing from 12-bit to 16-bit, extended the frequency response and expanded the control panel.

With the EMT 250 costing $15,000, the market once again demanded a cheaper alternative, and it initially came in the shape of Lexicon’s 224, which landed at half the price. From there, it didn’t take long for digital reverb to achieve ubiquity in professional and home studios around the globe, and the next couple of decades saw a raft of increasingly affordable and powerful models launched by an array of manufacturers including Eventide, TC Electronic, Roland, Yamaha and Alesis.

It must be said that the emulations presented by these unarguably wondrous devices didn’t often sound all that convincing, but their synthetic, glossy textures, unnatural characteristics and criminal over-use were hugely influential on the sound of music in the 1980s, from Phil Collins and every power ballad of the time, to Vangelis and Eno/Lanois. In the decade of excess, it seemed there was no such thing as too much reverb.

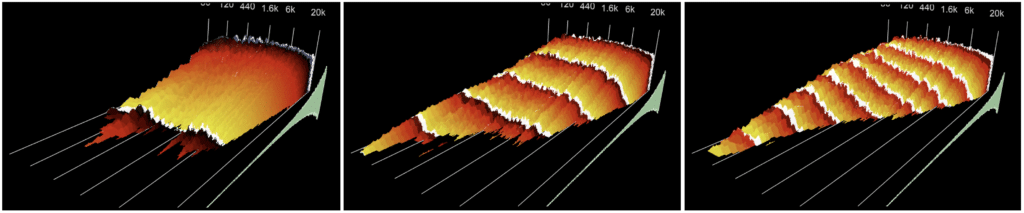

A huge milestone in the development of digital reverb hardware was hammered into the ground by Sony, whose 1997 DRE S777 unit blew our collective mind with the introduction of real-time convolution processing. Without relying on FFT techniques to lessen the load, it uses a brute-force FIR implementation using various custom silicon.

While regular algorithmic reverbs generate their imaginary spaces using networks of delay lines, convolution reverb uses impulse responses sampled from real environments and spaces to emulate them with unparalleled realism. The captures painstakingly taken by Sony stand as some of the finest ever made, and despite the efforts of some key reverb figures in the industry Sony have never been convinced to make them available for use in newer designs. You can read more about the differences in this article about convolution vs algorithmic reverb.

The pinnacle of digital reverb design to date is Bricasti’s M7 algorithmic processor. Released in 2008 it is still considered by many to represent the last word in hardware reverb, eclipsing what were the final designs of other great manufacturers like the Lexicon with the 960L or Eventide with the H8000, its beautifully organic-sounding tails and supernatural transparency genuinely competing with the physical fidelity of convolution. It has a wonderfully subtle approach to modulation, and is one of the most transparent reverbs ever made making it particularly suited to score mixing with a wonderful low end processor creating particularly convincing small rooms.